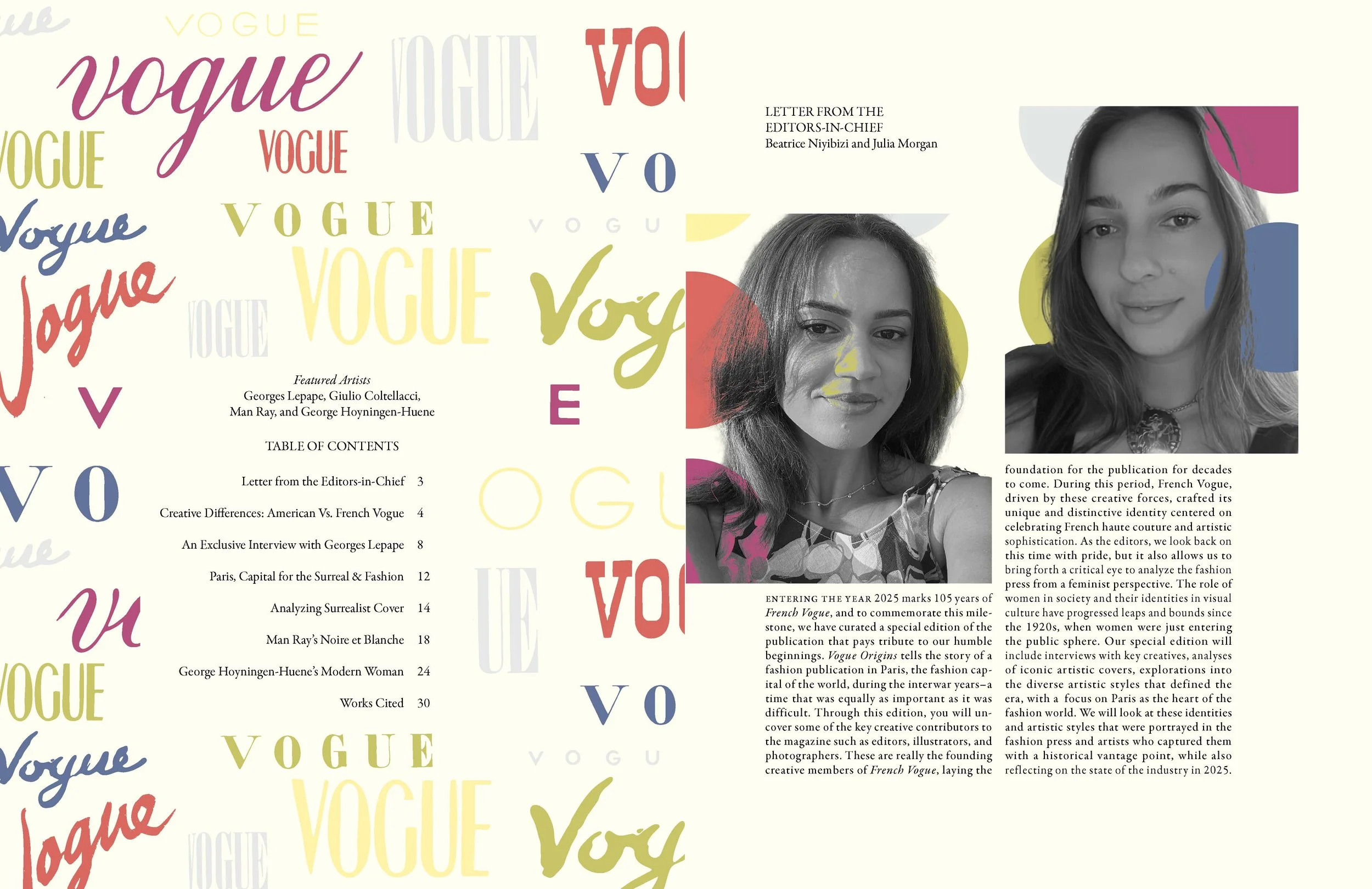

Concept: Vogue Origins, a Retrospective

Exploring Women’s Identities & the Creative Tensions of French Vogue in Interwar Paris

As a graphic designer, I find magazines to be a great source of inspiration, from the photography to the layouts of the pages themselves. The year 2025 marks 105 years of French Vogue, and to commemorate this milestone, Beatrice & I curated a special edition of the publication for our final project that pays tribute to its humble beginnings. The publication tells the story of French Vogue during the interwar years–a time that was equally as important as it was difficult. Through this edition, we uncover some of the key creative contributors to the magazine such as editors, illustrators, and photographers. For our project, we position ourselves fictitiously as the editors, where we look back on this time with pride while also bringing forth a critical eye to analyze the fashion press from a feminist perspective. Keep reading to check out my contributions to the magazine, which cover the intersection of Surrealism & Modernism with Fashion Photography.

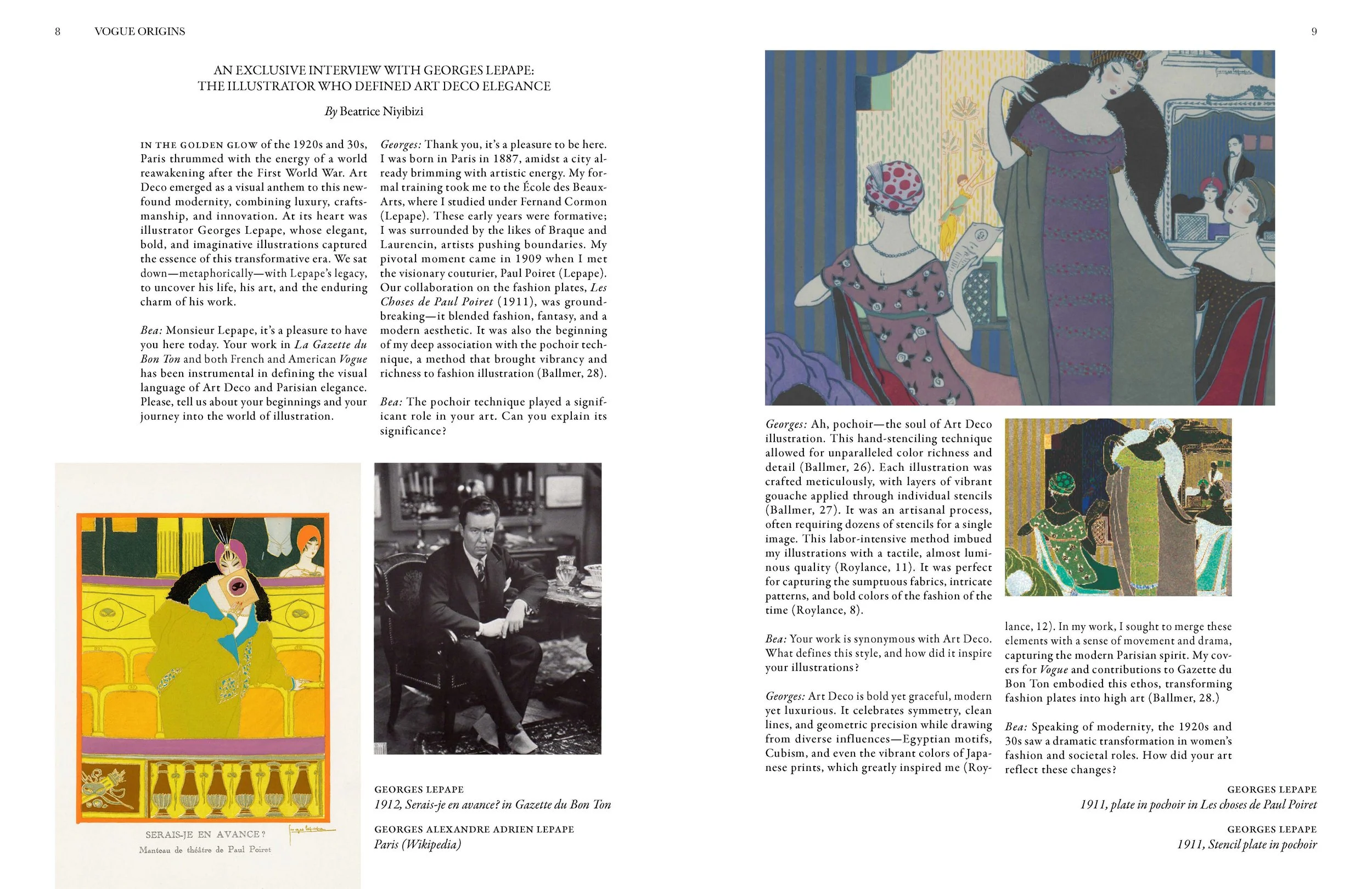

Noire et Blanche: A Look at Surrealist Fashion Photography and Women’s Roles

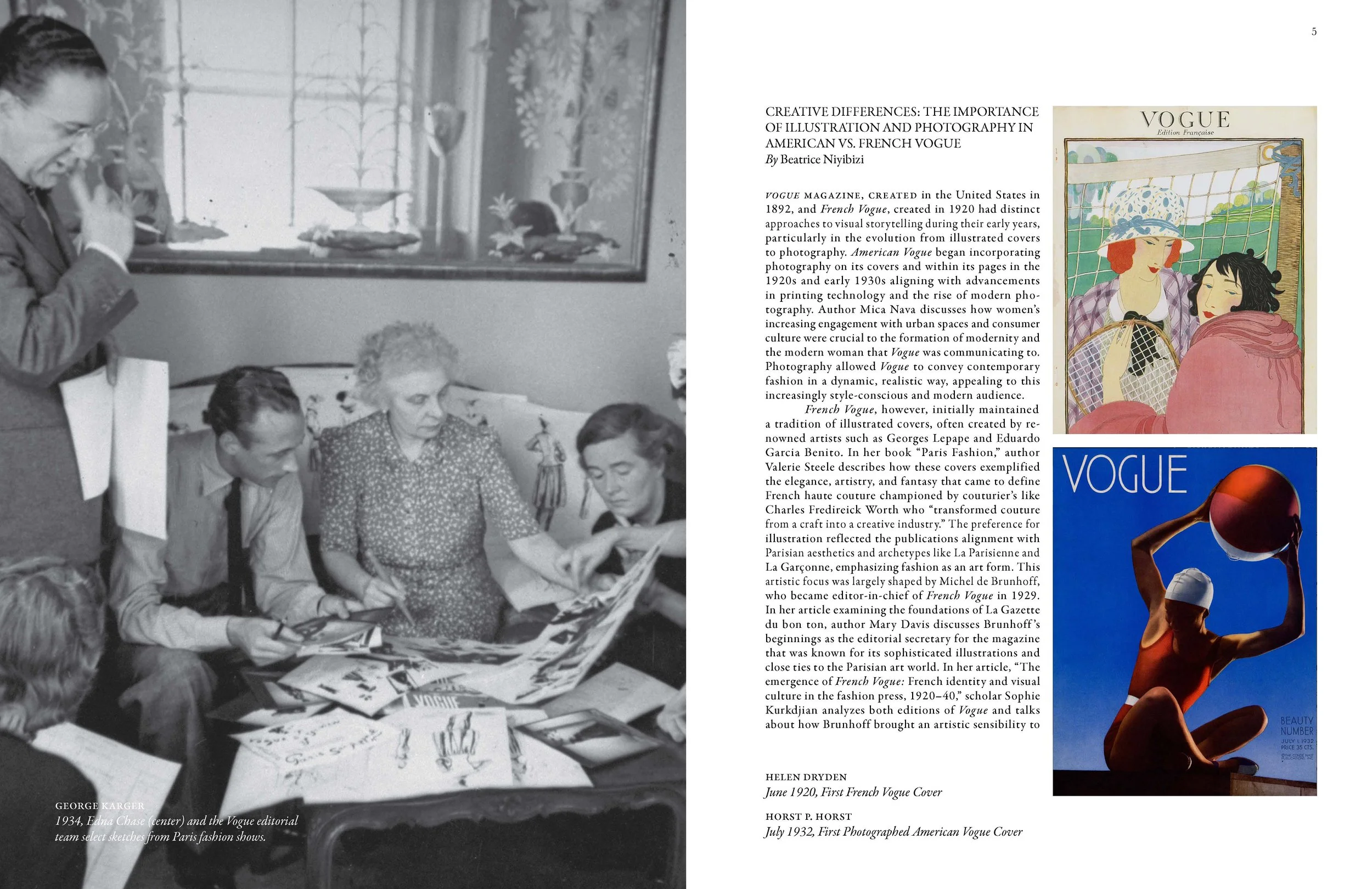

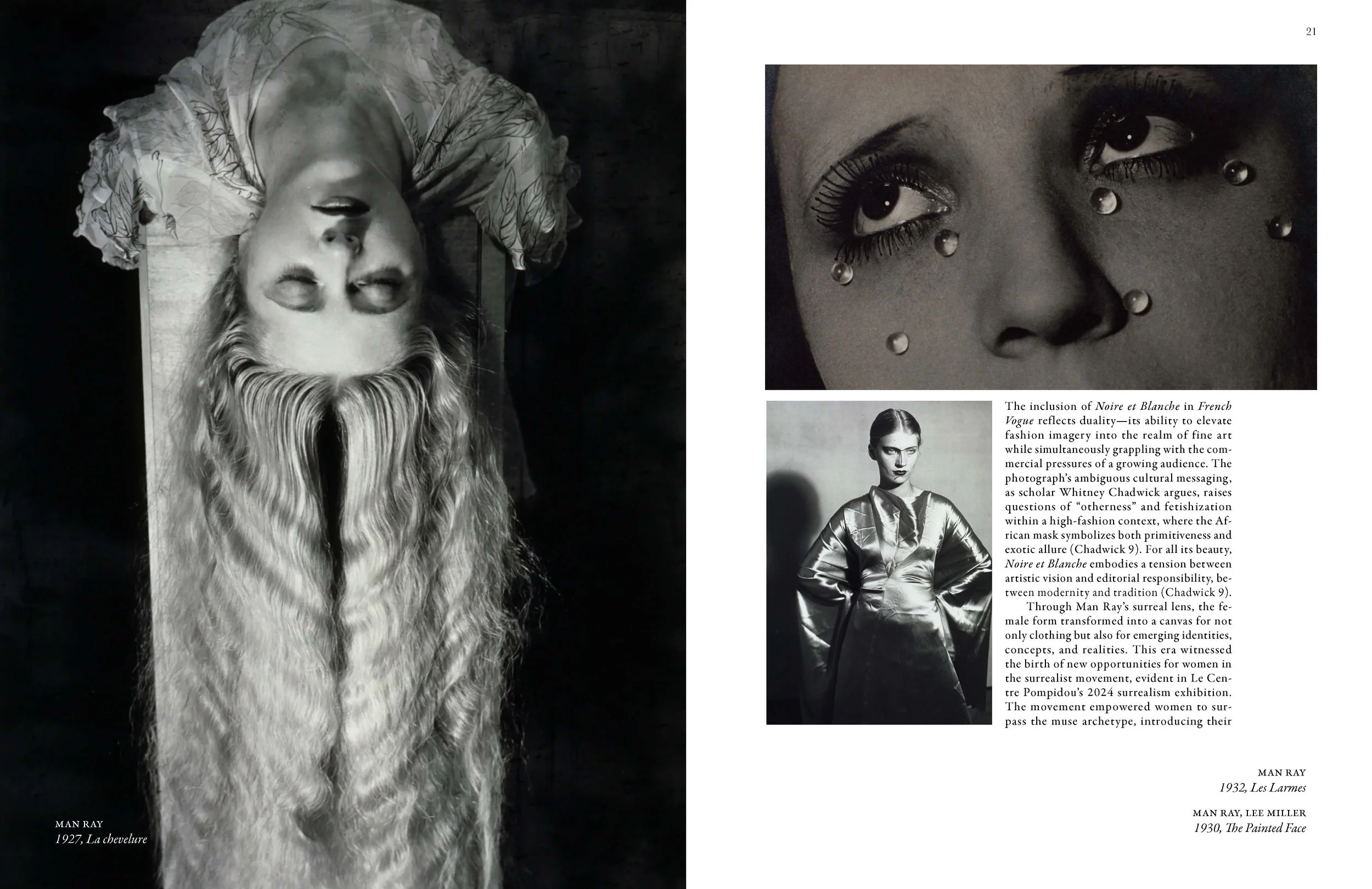

When Man Ray’s Noire et Blanche was featured in Vogue Paris in May 1926, its juxtaposition of a white model who is known to be his muse, Kiki Montparnasse’s pale face cradled beside an African mask captured both a surrealist ethos and the evolving identity of Parisian fashion (Lubow 75). For the French editors at Vogue, this photograph was an artistic statement that bridged avant-garde and haute couture (Kurkdjian 71). However, Across the Atlantic, American Vogue editors were driven by commercial concerns and saw fashion photography strictly as a tool to show garments clearly and appeal to a broader readership in a commercial sense (Kurkdjian 71).

Lubow recounts Man Ray’s lasting impression on fashion photography, Surrealism, and other artists and photographers, such as his assistant, long-time friend, and lover Lee Miller. Man Ray was called to art and the city of Paris from an early age, and though he self-identified as an artist and painter, he found lucrative financial success in photography and working with fashion magazines (Lubow 3). Unlike the Americans’ insistence on precision and detail to showcase a garment, Noire et Blanche disrupts expectations, embracing abstraction, contrast, and ambiguity. Man Ray brought this vision to fashion photography, where he fragmented and transformed the female form, creating images that both enchanted and unsettled (Chadwick 12).

The inclusion of Noire et Blanche in French Vogue reflects duality—its ability to elevate fashion imagery into the realm of fine art while simultaneously grappling with the commercial pressures of a growing audience. The photograph’s ambiguous cultural messaging, as scholar Whitney Chadwick argues, raises questions of “otherness” and fetishization within a high-fashion context, where the African mask symbolizes both primitiveness and exotic allure (Chadwick 9). For all its beauty, Noire et Blanche embodies a tension between artistic vision and editorial responsibility, between modernity and tradition (Chadwick 9).

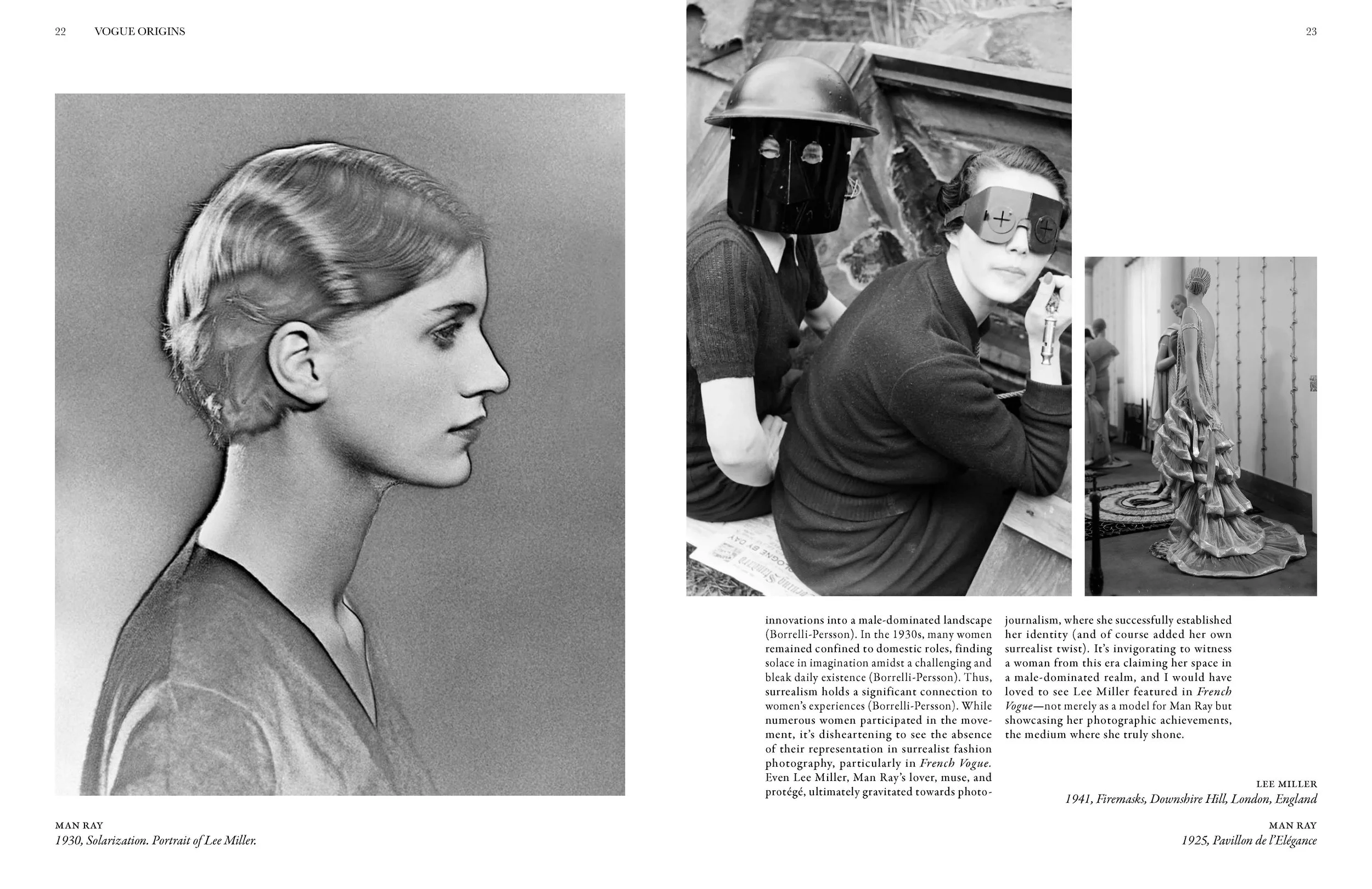

Through Man Ray’s surreal lens, the female form transformed into a canvas for not only clothing but also for emerging identities, concepts, and realities. This era witnessed the birth of new opportunities for women in the surrealist movement, evident in Le Centre Pompidou’s 2024 surrealism exhibition. The movement empowered women to surpass the muse archetype, introducing their innovations into a male-dominated landscape (Borrelli-Persson). In the 1930s, many women remained confined to domestic roles, finding solace in imagination amidst a challenging and bleak daily existence (Borrelli-Persson). Thus, surrealism holds a significant connection to women's experiences (Borrelli-Persson). While numerous women participated in the movement, it's disheartening to see the absence of their representation in surrealist fashion photography, particularly in French Vogue. Even Lee Miller, Man Ray’s lover, muse, and protégé, ultimately gravitated towards photojournalism, where she successfully established her identity (and of course added her own surrealist twist). It's invigorating to witness a woman from this era claiming her space in a male-dominated realm, and I would have loved to see Lee Miller featured in Vogue Paris—not merely as a model for Man Ray but showcasing her photographic achievements, the medium where she truly shone.

George Hoyningen-Huene’s Modern Woman

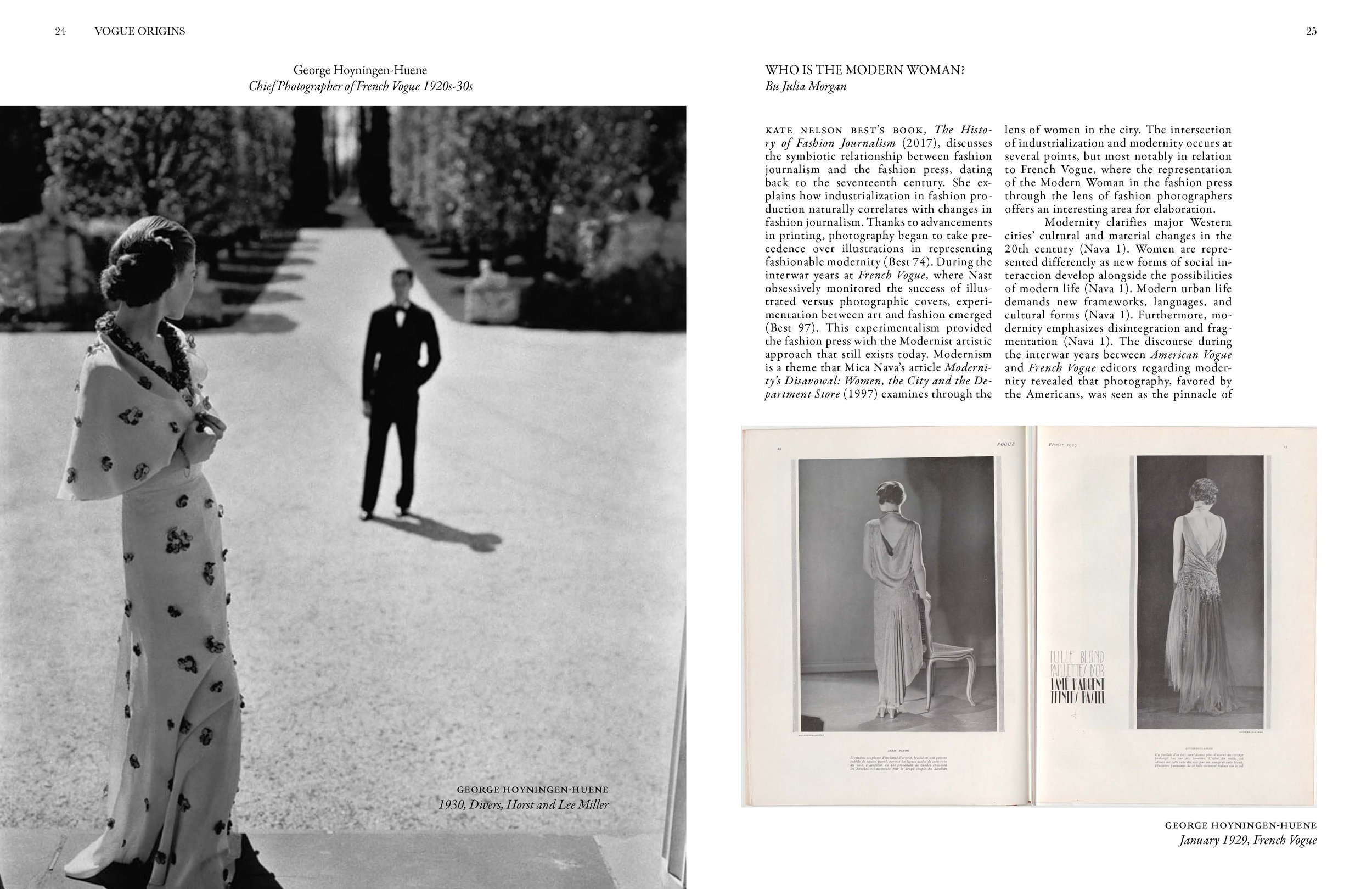

Kate Nelson Best’s book, The History of Fashion Journalism (2017), discusses the symbiotic relationship between fashion journalism and the fashion press, dating back to the seventeenth century. She explains how industrialization in fashion production naturally correlates with changes in fashion journalism. Thanks to advancements in printing, photography began to take precedence over illustrations in representing fashionable modernity (Best 74). During the interwar years at French Vogue, where Nast obsessively monitored the success of illustrated versus photographic covers, experimentation between art and fashion emerged (Best 97). This experimentalism provided the fashion press with the Modernist artistic approach that still exists today. Modernism is a theme that Mica Nava’s article Modernity’s Disavowal: Women, the City and the Department Store (1997) examines through the lens of women in the city. The intersection of industrialization and modernity occurs at several points, but most notably in relation to French Vogue, where the representation of the Modern Woman in the fashion press through the lens of fashion photographers offers an interesting area for elaboration.

Modernity clarifies major Western cities’ cultural and material changes in the 20th century (Nava 1). Women are represented differently as new forms of social interaction develop alongside the possibilities of modern life (Nava 1). Modern urban life demands new frameworks, languages, and cultural forms (Nava 1). Furthermore, modernity emphasizes disintegration and fragmentation (Nava 1). The discourse during the interwar years between American Vogue and French Vogue editors regarding modernity revealed that photography, favored by the Americans, was seen as the pinnacle of modernity, while the French—who preferred fashion illustrations to uphold artistic tradition—resisted this modernity (Kurkdjian 64). The debate continues regarding whether women were historically excluded from modernity, which primarily focuses on the public sphere, as traditional representations of women in the fashion press during this period confine them to the private sphere, engaged in domestic tasks (Nava 2). Nava argues that women were actually not excluded from modernity, with the site of the department store being the place where they were expressing themselves in the public sphere. Additionally, through the lens of the flourishing fashion photography industry in the interwar years, we can critique the Modern Woman as well.

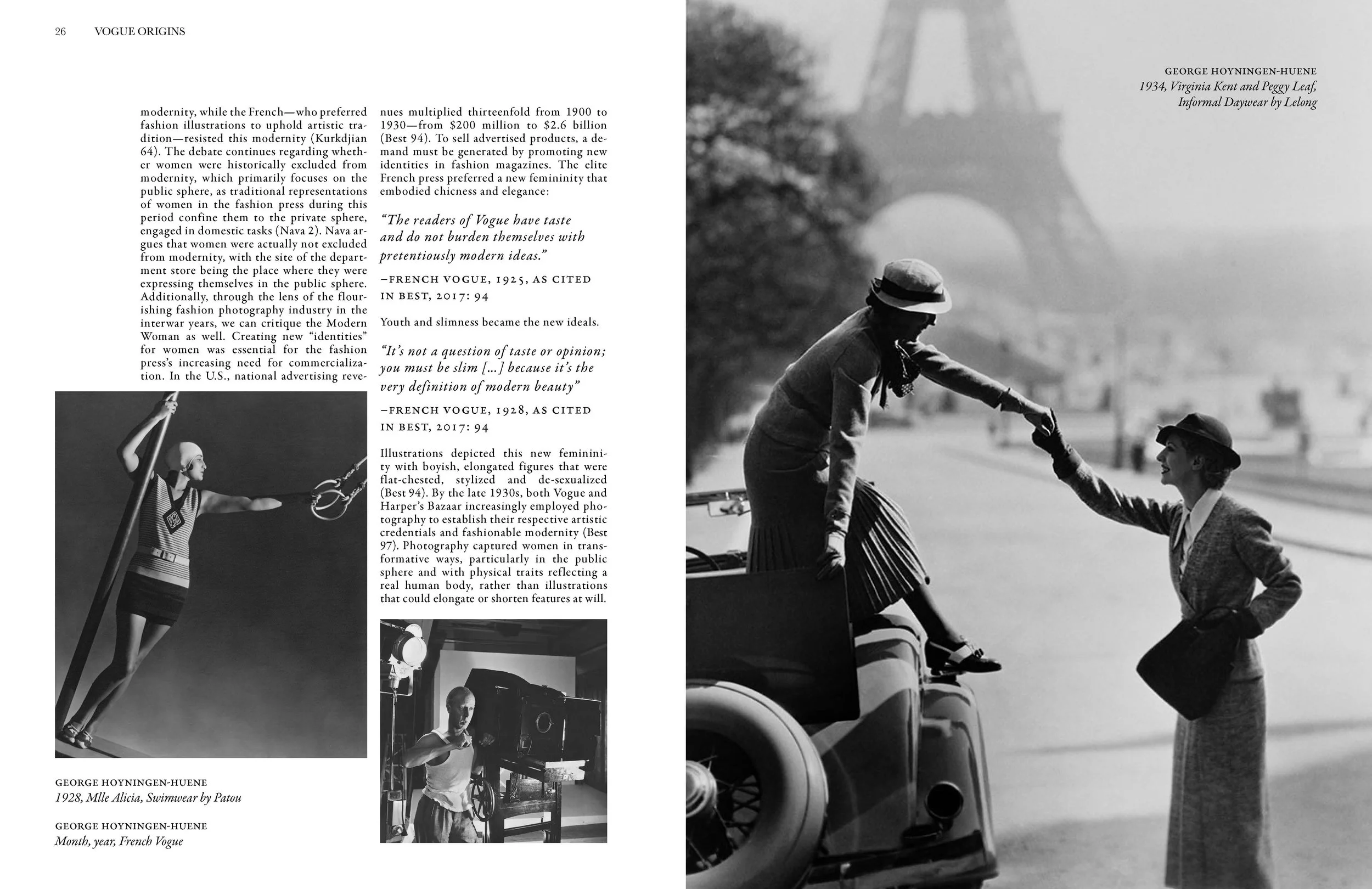

Creating new “identities” for women was essential for the fashion press's increasing need for commercialization. In the U.S., national advertising revenues multiplied thirteenfold from 1900 to 1930—from $200 million to $2.6 billion (Best 94). To sell advertised products, a demand must be generated by promoting new identities in fashion magazines. The elite French press preferred a new femininity that embodied chicness and elegance: “The readers of Vogue have taste and do not burden themselves with pretentiously modern ideas.” Youth and slimness became the new ideals. “It’s not a question of taste or opinion; you must be slim […] because it’s the very definition of modern beauty,” asserted French Vogue in November 1928 (Best 94). Illustrations depicted this new femininity with boyish, elongated figures that were flat-chested, stylized and de-sexualized (Best 94). By the late 1930s, both Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar increasingly employed photography to establish their respective artistic credentials and fashionable modernity (Best 97). Photography captured women in transformative ways, particularly in the public sphere and with physical traits reflecting a real human body, rather than illustrations that could elongate or shorten features at will.

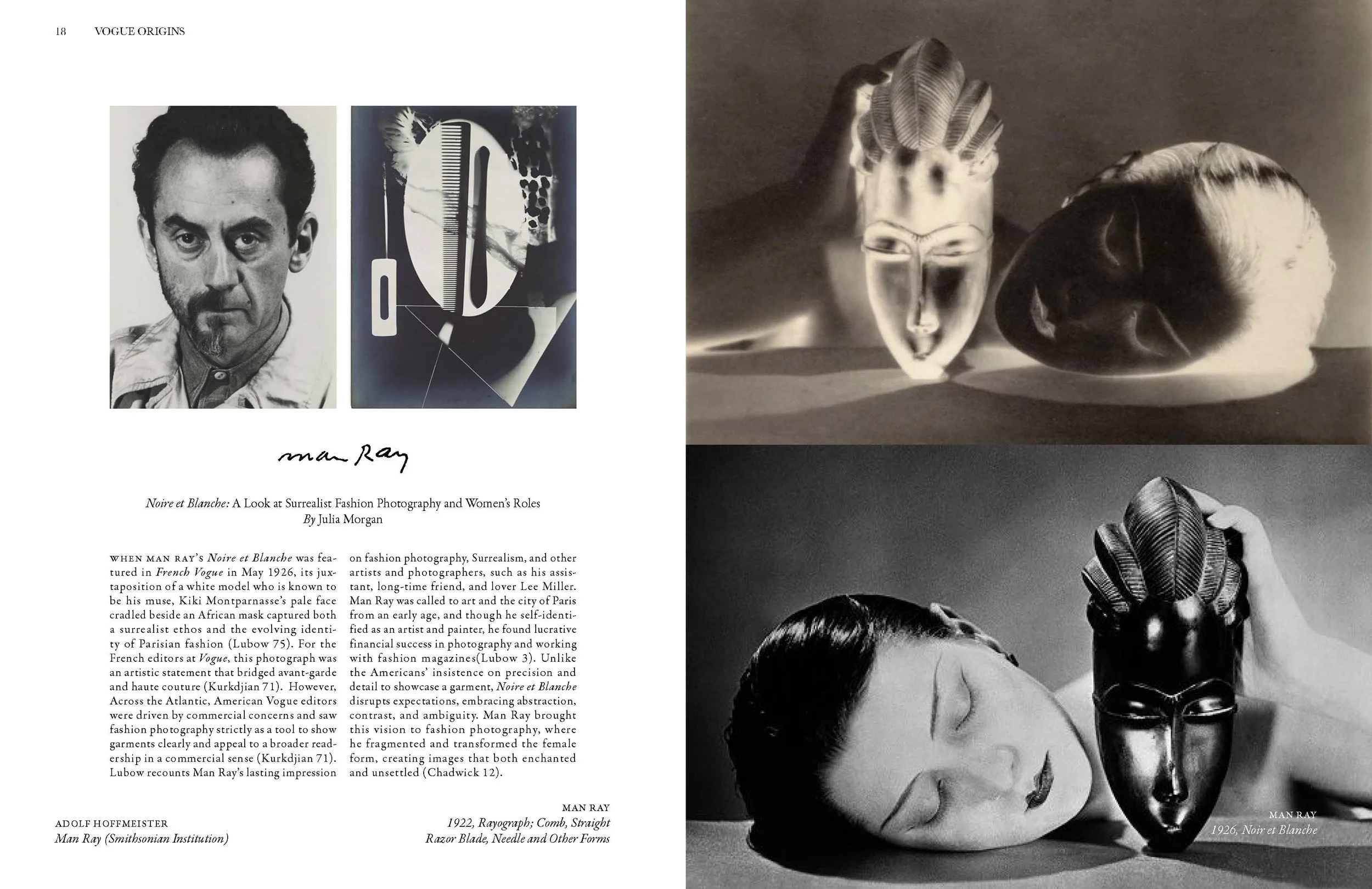

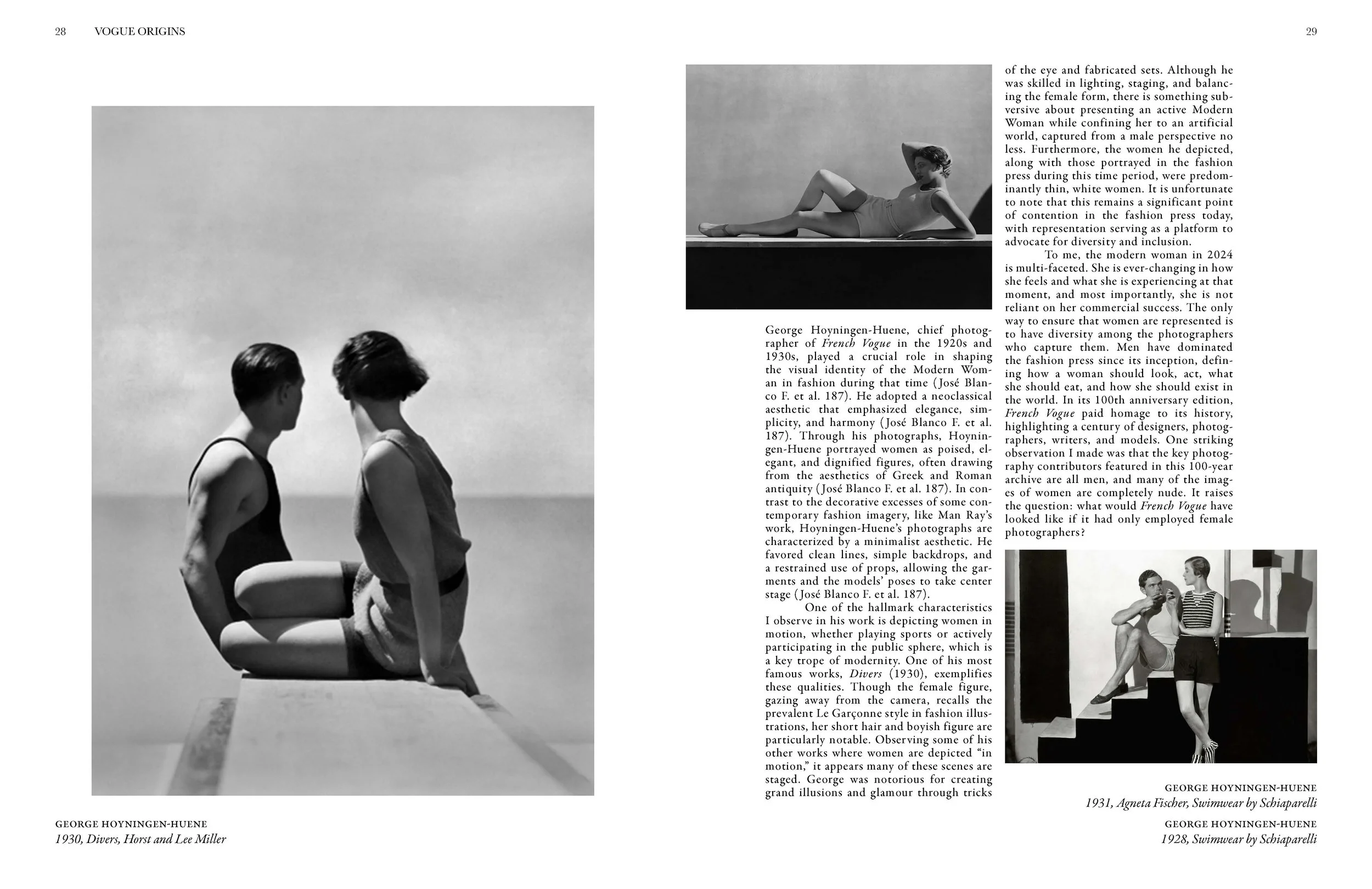

George Hoyningen-Huene, chief photographer of French Vogue in the 1920s and 1930s, played a crucial role in shaping the visual identity of the Modern Woman in fashion during that time (José Blanco F. et al. 187). He adopted a neoclassical aesthetic that emphasized elegance, simplicity, and harmony (José Blanco F. et al. 187). Through his photographs, Hoyningen-Huene portrayed women as poised, elegant, and dignified figures, often drawing from the aesthetics of Greek and Roman antiquity (José Blanco F. et al. 187). In contrast to the decorative excesses of some contemporary fashion imagery, like Man Ray’s work, Hoyningen-Huene's photographs are characterized by a minimalist aesthetic. He favored clean lines, simple backdrops, and a restrained use of props, allowing the garments and the models' poses to take center stage (José Blanco F. et al. 187).

One of the hallmark characteristics I observe in his work is depicting women in motion, whether playing sports or actively participating in the public sphere, which is a key trope of modernity. One of his most famous works, Divers (1930), exemplifies these qualities. Though the female figure, gazing away from the camera, recalls the prevalent Le Garçonne style in fashion illustrations, her short hair and boyish figure are particularly notable. Observing some of his other works where women are depicted “in motion,” it appears many of these scenes are staged. George was notorious for creating grand illusions and glamour through tricks of the eye and fabricated sets. Although he was skilled in lighting, staging, and balancing the female form, there is something subversive about presenting an active Modern Woman while confining her to an artificial world, captured from a male perspective no less. Furthermore, the women he depicted, along with those portrayed in the fashion press during this time period, were predominantly thin, white women. Unfortunately, this remains a significant point of contention in the fashion press today, with representation serving as a platform to advocate for diversity and inclusion.

To me, the modern woman in 2025 is multi-faceted. She is ever-changing in how she feels and what she is experiencing at that moment, and most importantly, she is not reliant on her commercial success. The only way to ensure that women are represented is to have diversity among the photographers who capture them. Men have dominated the fashion press since its inception, defining how a woman should look, act, what she should eat, and how she should exist in the world. In its 100th anniversary edition, French Vogue paid homage to its roots, highlighting a century of designers, photographers, writers, and models. One striking observation I made was that the key photography contributors featured in this 100-year archive are all men, and many of the images of women are completely nude. It raises the question: what would French Vogue have looked like if it had only employed female photographers?